Accessing just the right kind of help for people suffering without shelter is a challenge for the staff at Blanchet House. Visible homelessness is witnessed daily outside the cafe windows yet the individuals experiencing it remain invisible to society.

By Hannah Bachman and Jennifer Ransdell

The floor-to-ceiling windows lining Blanchet House’s free café give us a view of people navigating their day. Many people we serve meals to are houseless, so after dining with us they have nowhere to go. Guests stake claim to a small area of the sidewalk where they curl up or lean against our building to wait for the next meal.

As café staff, we see so much suffering from our windows. We try to connect with people, give what we have, and help in any way we can. There are times when we feel at a loss for how to help. We make phone calls to try to connect people to services like shelter or medical care. Often these phone calls end with the person in the same position as before–alone on the sidewalk, cold, suffering from injury or illness, dirty because there is nowhere to clean up, and left to battle what might come in the night.

A volunteer serves a meal to a guest in Blanchet House’s free cafe.

Our Regulars

Just like any other neighborhood café, Blanchet House has regulars. Some meal guests we know a lot about, and some we know nothing about. Seeing the same folks day after day builds familiarity and comfort between us. It’s hard not to feel kindly toward someone you see every day, even if all you exchange is a quick nod or “hello.”

We know that there are people who stay in our neighborhood so that they can be close to our cafe. It’s not just the meals that people stay close to, though—they stay for the safety, comfort, consistency, and sense of home they get while inside our cafe.

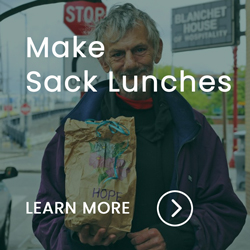

Our three daily meal services–breakfast, lunch, and dinner–are one hour long. When service is over, we must ask our guests to exit the café so that we can feed an in-house meal to shelter residents living with us. We also need time to clean the cafe and complete other work before we re-open our doors. We also offer clothing, hygiene kits, and to-go sack lunches when we have them available.

When we close the café doors, many diners return home to a nearby tent, they are part of the visible homelessness seen in our community. Others return to temporary shelters, cars, or low-income apartments. But what home looks like varies widely among our guests.

Visible Homelessness: A Doorway Is Her Home

One regular diner, Linda, age 60, rarely strays beyond our block. She sleeps in one of our doorways every night, with only a tarp and several layers of coats that we’ve provided her. We try to talk with her but it’s hard to understand what she’s saying. We can make out that she’d like a cigarette or coffee, her name, and her age, but not the specific resources she needs to get off the street.

Although many of our guests live outside, Linda is an anomaly. We see her every day, and our staff feels a sense of protection over her. ‘Have you seen Linda come in yet today?’ we ask each other. ‘Did Linda get any dinner?’ We can’t help but insert ourselves into her well-being because she seems physically fragile. And we’re aware of how much she depends on us for safety and survival.

Linda seems to be utterly alone. She has no possessions, no wallet, and no ID. She turns down our offers to get her a tent or a ride to an emergency shelter. Every attempt we’ve made to connect Linda to services that might offer long-term help is thwarted by inflexible rules and bureaucratic obstacles. Because Linda is only 60, she doesn’t qualify for social security or Medicare.

Outreach workers visit with her when we call but they are unable to get her off the street. We don’t just wonder how much longer we can be told no—we also wonder how much longer Linda has left.

When the weather got really bad in January, Linda reluctantly accepted transport to a warming shelter in far southeast Portland. She stayed there for a few days, and it was the longest she’d been away from us in months. When she came back to Blanchet House because she had nowhere else to go, she told us she was starving. The emergency shelter had only served breakfast. Although she had a temporary bed indoors, she didn’t have regular access to hot meals or familiar faces.

People sleep on the sidewalk outside Blanchet House.

Left Outside

When the next snowstorm came, we asked her if she’d like us to call a cab to a warming shelter, as we’d done before. Linda refused. In her mind, staying indoors meant sacrificing meals. She chose food and the familiarity of our sidewalk.

Linda isn’t alone in preferring to sleep on the sidewalk to a mat on a shelter floor. A 2019 survey of 180 people experiencing homelessness in Oregon found that the top barriers to using shelters were personal safety and privacy concerns, restrictive check-in and check-out times, overcrowding, and unsanitary conditions, reports KGW news.

Our work is predicated on hope, but sometimes it’s hard to remain hopeful for Linda. Blanchet staff fear coming to work one morning and finding Linda no longer alive. But thankfully this hasn’t happened yet.

Among our highly transient diners, Linda is a beacon of unflappable endurance. And just as Linda refuses to quit, so do we.