Nonprofit social service providers need guidelines to compassionately and equitably triage when resources are scarce.

By Jon Seibert

I was recently listening to “Radiolab,” one of my favorite podcasts, about how we triage people in need of help during times of crisis. The podcast episode “Playing God” dove into the challenges medical providers face while deciding which lives will be saved in war zones, hospitals, and natural disasters.

Triage is a French word. It’s been used for at least a couple of hundred years to describe a morally challenging process of determining who receives care when resources are scarce.

The moral implications of medical triage are, to say the least, complicated. Do we first help those in the most need? Should we make decisions that create the “greatest good” such as preserving the lives of people with the most years left to live? Do people with certain skills, such as first responders, get help first? Do we set up a lottery system, or go on a first-come, first-served basis? The answers will vary from person to person.

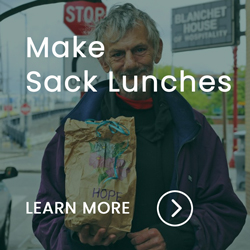

In listening to stories of doctors making tough decisions, I was reminded of the challenging decisions my colleagues and I make while serving people experiencing homelessness in Old Town, Portland. The need for aid is overwhelming. People knock on the doors of Blanchet House 24 hours a day asking for food, water, medical care, hygiene services, shelter, and sleeping supplies. We try to meet the needs of many, but our capacity is not unlimited.

Since I began serving at Blanchet House, we’ve nearly tripled our paid staff. As we’ve grown more capacity to serve, we continually discuss how to adjust our protocols to determine when we can fulfill a request for help and when we sadly cannot. It’s painful to tell a suffering person in front of you that you cannot help them.

I’ve met many compassionate people who give their time to social service organizations to help alleviate suffering. They attempt to meet the needs of everyone they encounter, breaking their backs to fulfill every request. Many people burn out this way, volunteers and professionals alike, sometimes leaving social services for good. Some of our peer agencies have had to close or stop services as they are unable to keep up with staffing demands as the crisis on our streets continues.

A volunteer at Blanchet House selects a pair of donated shoes to give a guest in need.

Establish Triage Guidelines

In order to serve our guests and staff in the best way possible we must establish rules of engagement. We need guidelines for when we go the extra mile to help someone because we know that it’s not always possible. And we want to serve equitably and sustainably.

In a recent email thread amongst staff, we shared that the same individual has been given at least four pairs of shoes over multiple weeks. They continue to show up to our door barefoot even on a 50-degree rainy day. Maybe their last pair were stolen, soiled, or sold. It’s also possible that their mental state caused them to take off their shoes and lose them. The challenge is that right behind is another person in need of shoes. And another. But we only have one pair left in a popular size. We must perform triage and determine who needs shoes more.

If a person asks for shoe day after day, do we keep providing them, knowing that means another person won’t get a pair? At some point, do we have to decide that this individual can’t have any more pairs of shoes? How do we balance being a place without judgment with the fact that we need to assess how to efficiently deliver a limited inventory of shoes?

I used to think the answers to these questions were simple. Now, they keep me up at night.

The “Radiolab” podcast concludes that the challenge inherent in triage when resources are scarce is its connection to the deepest levels of humanity. For a compassionate person, there can be no one right answer to when not to help another person.

“You have a God role, and nobody fits it,” said “Radiolab” co-host Robert Krulwich.

A God role that gives you the authority to decide whether someone gets a blanket or not on a cold day in January can put you in a position to go against your gut instincts. If we continue to have to triage situations of life and death, we will eventually burn out from this internal conflict.

Guests wait in line for food, clothing, shoes, and sleeping essentials at Blanchet House. Photo by Justin Katigbak.

How We Triage With Scarce Resources

Here’s what we’re doing at Blanchet House to avoid triaging on the fly and serving more equitably:

- We have expanded staff and volunteers including adding peer support specialists.

- To give people a clearer understanding of what we can provide them, we now have a schedule for when we hand out supplies. This schedule reduces stress and confusion.

- The best way to avoid triage is to increase resources. We increased our ask to donors for sack lunches and hygiene care kits. This helps us better balance our inventory.

- We built partnerships with peer agencies both nonprofit and governmental, to connect more people to life-saving resources.

But it’s not enough. We still need to make hard decisions every day, because we are in the midst of a homelessness crisis. More money is needed across the human services sector, and essential staff positions remain unfilled. Without professional staff to regularly deliver support to our most vulnerable citizens, we can’t expect a significant reduction in homelessness. And we will continue to put employees and volunteers in morally difficult situations where they determine who gets the last sleeping bag. This way of serving is not sustainable.

You can help by supporting Blanchet House and partner agencies by donating and volunteering.