By Scott Kerman

I was recently asked, “What is the most important thing Oregon’s next governor should know about houselessness and housing insecurity?”

My answer? Trauma.

Some will disagree with me, saying that the critical issue is the lack of affordable housing.

And they are right.

Others may say the lack of livable wages, coupled with the crushing expense of childcare and health care, are the reasons for homelessness.

They are correct, too.

Other correct answers include over-incarceration, lack of appropriate mental health and addiction treatment, the treatment of addiction as a crime rather than a public health concern, and an inadequate social safety net for underserved communities, including seniors and people with disabilities. These issues all contribute to our homelessness crisis.

Also, let us not gloss over the debilitating effects of generational and systemic poverty, discrimination, and racism. These social ills are significant causes of homelessness too. But I believe recognizing the role trauma plays in understanding homelessness is the most important issue for the next governor.

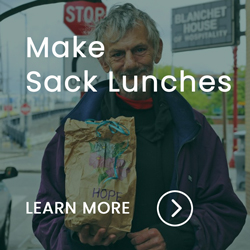

At Blanchet House, an Oregon nonprofit serving people experiencing homelessness, food and housing insecurity, and addiction, the lingering and deepening effects of trauma are foremost in our minds. For many people, trauma exists at the heart of their need for aid and social services.

How does trauma lead to housing insecurity?

Trauma, particularly experienced as a child, can lead to substance abuse and mental illness. People use substances to dull the pain of depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress. Addiction can exacerbate mental illness, sometimes even inducing psychosis.

At Blanchet House, we hear heartbreaking stories daily from our guests – stories of generational trauma, child abuse, neglect, and domestic violence. A resident of our transitional shelter program told me his story of coming out as gay to his family. He experienced severe physical abuse as a result and ran away. This led him to drug use and then to crime as a way of supporting his drug use. He became houseless.

Sadly, his story is shared by many in the homeless community.

Homelessness itself is traumatic. A person experiencing homelessness often lives in a perpetual fight or flight mode, which has profound effects on their brain chemistry and physical health. And the longer someone experiences homelessness the more difficult it is to find the right long-term supportive housing for them.

In many ways, the community we serve is not a homeless community but a traumatized community. These individuals live unsheltered without regular access to proper hygiene, sanitation, and treatment. This reflects how our society cares or does not care for our traumatized neighbors.

It is imperative that we seek ways to recognize and address trauma. Trauma compounds like interest. Add to this mix the impacts of a pandemic, which have resulted in houseless citizens being shut out of and turned away from resources that previously provided relief. It is no wonder that we see great levels of despair, hopelessness, and even hostility among the people Blanchet House serves today.

Focusing on trauma compels us to see homelessness not as a cause of problems – tents, trash, vagrancy, despair, and hostility – but as the result of something more profound, something more human.

Dr. Gabor Maté, a leading expert on addiction, trauma, and houselessness says, “We have to see each other for what’s happened to us and not what’s wrong with us.”

This way of thinking could revolutionize how our community approaches housing insecurity and those who experience it. It certainly is how Blanchet House, and our colleagues approach our work. We recognize the humanity within the person seeking our aid and help.

I encourage Oregon’s next governor to consider the pain people experiencing homelessness are in when working to address housing insecurity. This level of inquiry will inspire policy that addresses root causes of homelessness lead to better outcomes.

Nonprofits like Blanchet House need backing for projects like a collaborative peer support program. Through this project, shared teams of professionals with lived experience will provide crisis de-escalation and referral services to people experiencing homelessness. We need a commitment to funding services like this and Portland Street Response so that the police are not responsible for resolving mental health crises.

Additionally, more funding for longer-term transitional shelters is needed. Blanchet House and Blanchet Farm offer a place to gain sobriety, rebuild physical and mental health, and find work and affordable housing.

These kinds of programs are an essential bridge from trauma to permanent housing for many people experiencing homelessness in our community.

Scott Kerman is Executive Director of BLANCHET HOUSE OF HOSPITALITY, which provides meals to persons experiencing housing insecurity in Old Town, Portland, as well as long-term transitional shelter in Old Town and at Blanchet Farm in Carlton, Oregon.

This article originally appeared in The Oregon Way.

The Oregon Way blog features opinion pieces from contributors across the state and the political spectrum with the intent of identifying common values among Oregonians.