By Emily Reiling

Until a month ago, I had never been to the Northwest. It called to me as a distant concept—the mountains and coast, the coffee culture and music scene, the quirkiness and earthiness (even before I knew I was moving to Portland, my ideas of the region were decidedly Portland-centric). It offered such a distinct contrast to the places I have called home for the past 22 years, a change of pace and mind.

By the time senior year of college rolled around, I had long decided that I wanted to commit my first postgraduate year to service. Working with marginalized populations suffering from systemic injustices and inequities could have taken many different forms in different places, but for me it meant serving people experiencing hunger and homelessness. It meant remaining in the United States with care to neither impose upon nor burden a community I intended to aid. It meant living out values of solidarity with the populations I serve in ways that extend beyond work hours.

It meant living out values of solidarity with the populations I serve in ways that extend beyond work hours.

With these wishes in mind, I applied to Jesuit Volunteer Corps (JVC) Northwest, a program that that places volunteers in full-time service positions in five states across the Northwest for year-long commitments. As an added bonus, the program allowed me to move to a part of the country that seemed new and exciting. I decided to go for it and see what happened—a theme that has consistently appeared alongside my major life choices.

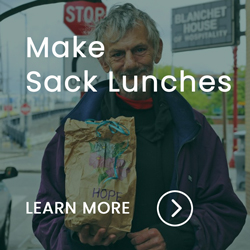

JVC Northwest matched me with Blanchet House of Hospitality, located in Portland’s Old Town/Chinatown neighborhood. Blanchet House is known for its meal program, combating hunger and serving all, without question, in a manner that seeks to respect and restore the dignity of each guest—human beings who are often not treated as such. The other half of the mission, one that is often overlooked next to the massive scale of the meal services, is the transitional housing program at Blanchet House and Blanchet Farm in Carlton, Oregon.

Portland From My Window

I landed in Portland in August amid a summer “heat wave” that felt more like an early Fall compared to the stifling humidity that I had left behind. As anyone who has flown into PDX when there is still light in the sky knows, the views of Mt. Hood and surrounding rivers and ranges as the plane descends are stunning. I was hooked on Portland before I’d even arrived.

I left the airport on a bus filled with the new class of Jesuit Volunteers, excited and anxious and everything in-between, still taking in views of trees that seemed bigger and greener and different if only because of the distance of the trees I’d known.

Then my eyes adjusted, and all I could see were the tents under the overpasses, the shopping carts along the highway bursting with people’s complete material possessions. Already it was nothing like I had seen at home; tents were not typical, neither were camps, groups, the concentrated setups. At least, not in places that were so visible in any part of town. I was hurting for Portland before I’d even arrived.

I knew from the beginning that I’d be staring this privation and injustice in the face every day, but these sights were disturbing nonetheless. As we drove through Portland for the first time on our way to the house we’d live in for the year, we grew discernibly quieter with the passing of every tent, cocooned figure, and makeshift structure raised anywhere apparently deemed habitable.

The sheer number of people who were visibly desolate—I’d never seen anything like it back East.

The sheer number of people who were visibly desolate—I’d never seen anything like it back East. The numbers, maybe, of people who came to meal services or day shelters or other service providers were comparable between the coasts. Nowhere have I observed the number of people visibly experiencing homelessness, living chronically unhoused and unsheltered.

Settling In

After living here for a few months, I’ve learned that the housing crisis that continues to grow in Portland is acute. Having a job is not a significant shield from the streets; one missed paycheck, one medical emergency or unforeseen difficulty can be the difference between having a home or not. In the West, there are substantially less shelters and units to keep people who can’t access longer-term housing from resorting to camping or sleeping in public spaces; according to a 2017 article published in the Seattle Times, New York City has more people in shelters than Washington, Oregon, and California combined.

It is difficult to confront these facts as I encounter more of the faces and stories behind the statistics every day. Then I walk into Blanchet House, or get home to my community of fellow Jesuit Volunteers and hear about their days and the good, difficult work they do, and I feel hope. People are trying, and lives are changing for the better every day. None of us are changing the huge systemic inequities, the unjust policies, the degrading and inhumane treatment of human life—not yet—but we are transforming individuals’ lives. A plate of warm food is life to someone who has not eaten in three days. A smile and eye contact earned from a guest who faces the trauma and fear of sleeping on the streets every night is radical.

Seeing people on the streets every day, serving them during what may be the lowest points of their lives, I fear that I will become desensitized. Before, I had to seek out this work. I had to go to a specific part of town at a specific time to reach it, to connect. Now, I just have to walk outside. It’s not hidden away here to the extent that it is in other cities because it can’t be—I haven’t yet decided if that’s better or worse. The injustice stares you down every day, makes you look it in the face. Every time you look at a person who is suffering, you are forced to turn inward. Or you are numbed to it. I hope I never understand it to be normal.

Emily Reiling served as the Volunteer Coordinator for a year while a Jesuit Volunteer with AmeriCorps. You can sign up to volunteer at Blanchet House here.